2010, Ireland

The Hole Made by a Waterfall, Ireland

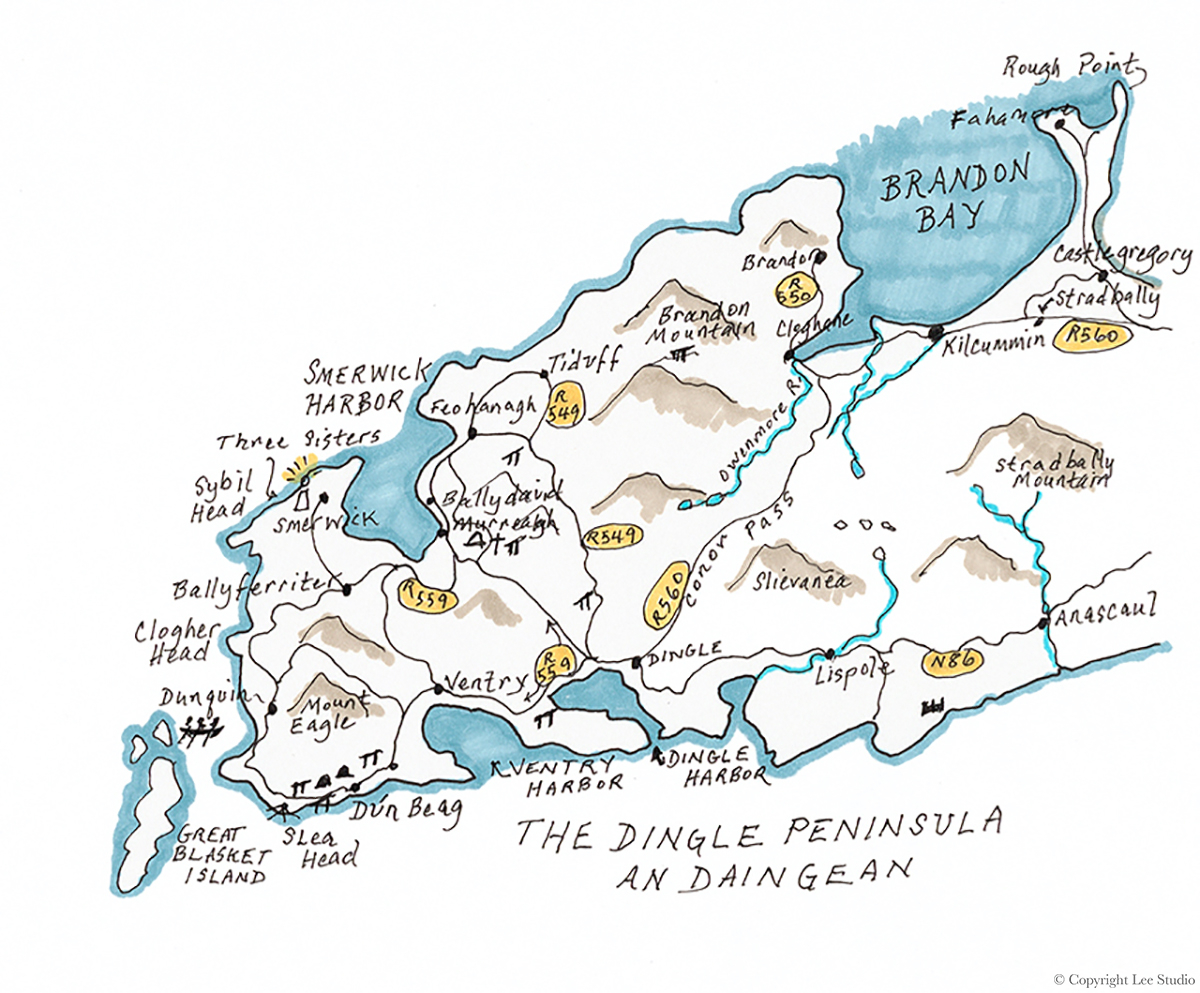

By staying for two months in the same apartment in the off season, I hoped to experience a taste of authentic day-to-day life in Ireland. I chose the town of Dingle because it was small enough to walk across, large enough to host a variety of restaurants and shops, close enough to drive to Shannon Airport in two hours, and loaded with archeological and historical sites. Charming hamlets tucked in around stunning landscapes and extraordinary seascapes of this mountainous southwest-pointing peninsula. I had met some fine people there in my earlier travels, and I hoped to gain a more in-depth knowledge of them and others. To punctuate my solitude, valuable as it was, various family and friends from home brought their welcome company and good cheer.

By the end of my long stay, I was on the verge of developing a sense of community there in Dingle. I had met several kind and hospitable residents and joined a local art group. But having lived in a northern Michigan town of eight hundred people where I raised my family for the last twenty-four years, I knew what it meant to be considered a local and I had few illusions that I would be accepted as part of the community. In my town, it took twelve years for the locals to stop calling my house by the name of the people who had lived there before the people from whom I’d bought it. And they had lived there eight years before I moved in. In Ireland, it would be enough for me if the locals felt I added positive qualities to their existence, and they treated me with kindness and tolerance.

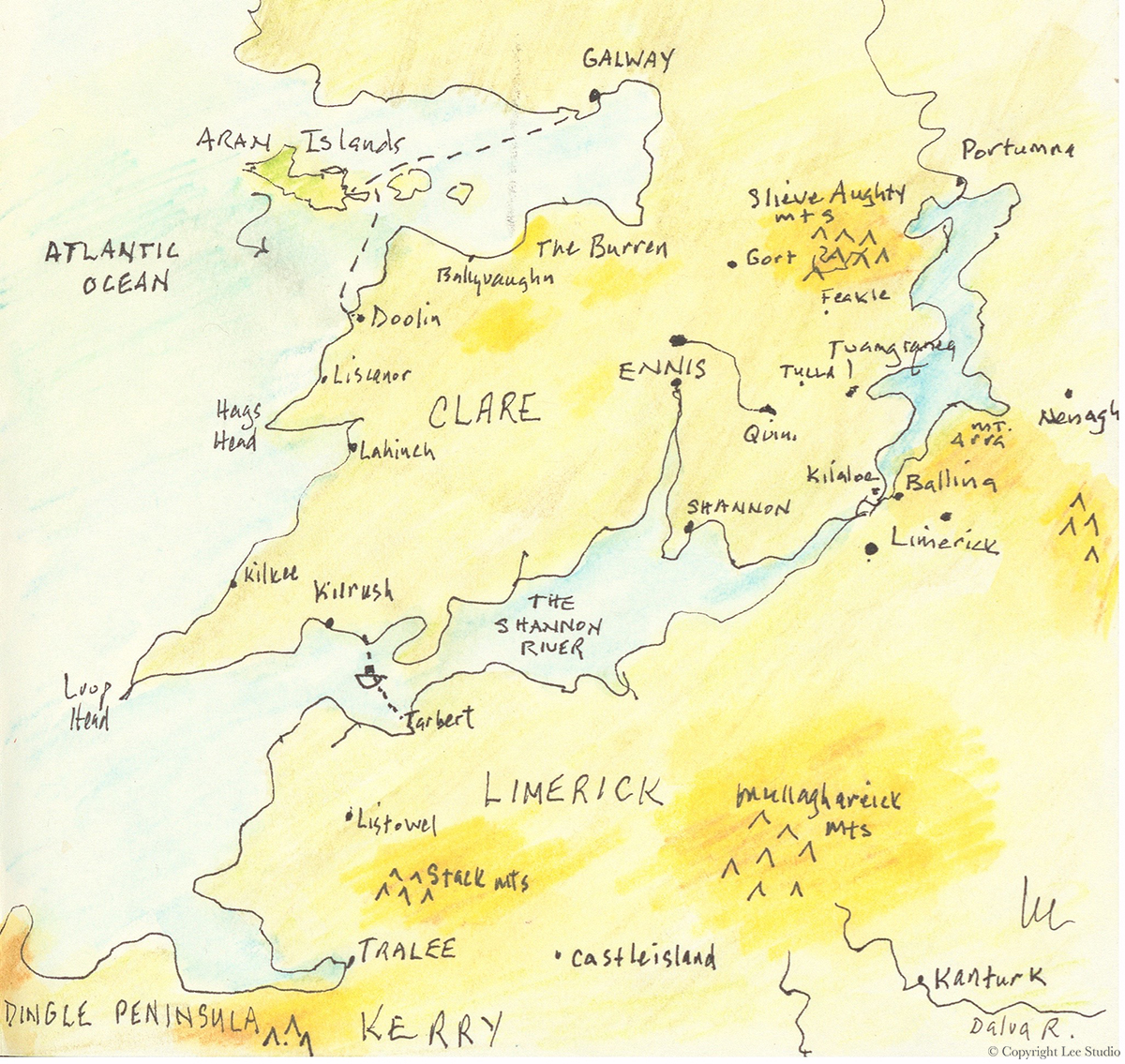

Travel plans began when my friend, Shirley, invited me stay with her, her adult children, and her sewing group at Ballyhannon Castle in Quin, County Clare. The wealthy Phillips family from America converted the old tower and stables into a self-catering rental property in 1970.

Originally, the castle, a tower house, was built in 1490 by the MacNamaras who retained it for centuries. However, in the mid-1500s, Queen Elizabeth I controlled ownership in Ireland, and the castle might be granted to an Earl in one act, and taken away if she so chose, and so it passed between the MacNamaras and the O’Briens, depending on who was in her favor.

Friday, 10 September 2010

From Michigan, to Boston, to Shannon Airport

To Ballyhannon Castle, Quin, County Clare, Ireland

Ten of us stayed at the castle for a week as we explored the country from there. The castle itself had been restored for lodgings but retained the same original dank, dark charm of the 15th century tower house of Clan MacNamara and O’Brien.

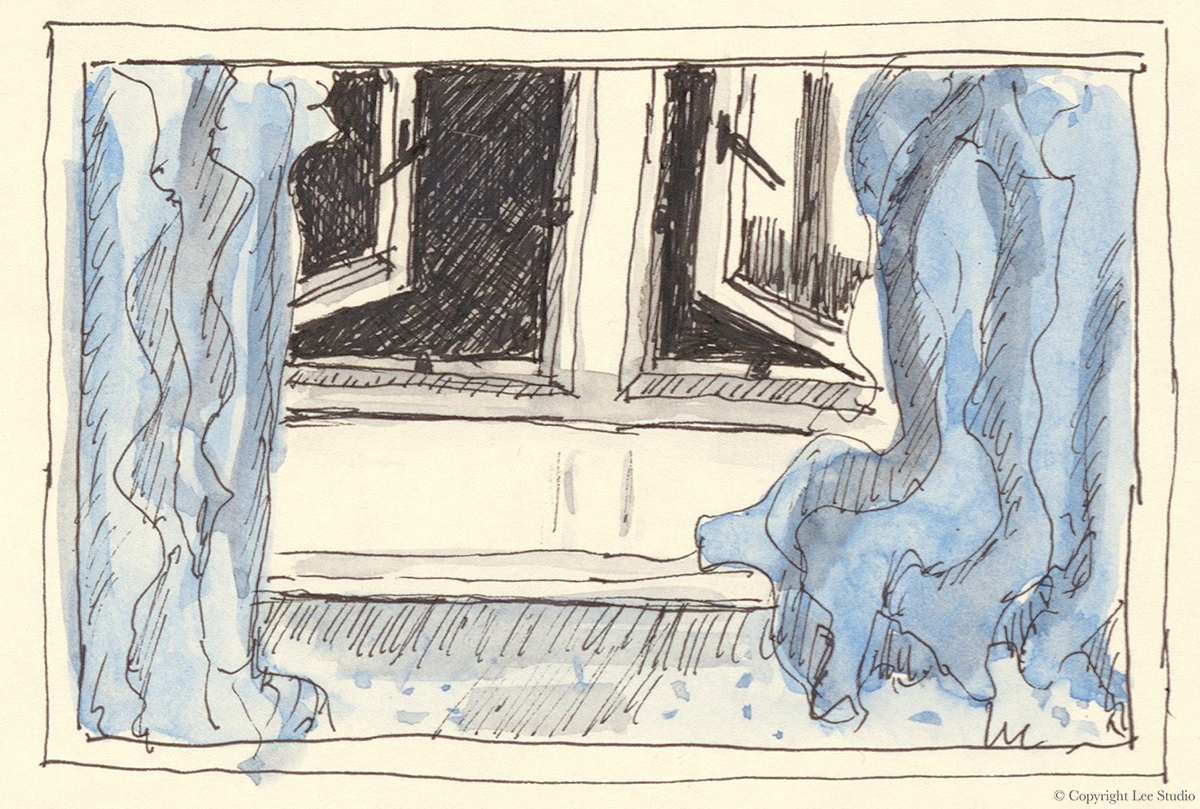

The circular winding stone stair rose four stories. When you stepped over the door sill of the bedrooms, it was not onto a landing— your foot came down onto one of the triangular worn smooth sloping stones of the staircase. It was quite scary and dangerous. The top room was magnificent with high-timbered ceilings. Draperies surrounded the bed tucked against the wall in the huge circular space.

All had occupied their rooms by the time I arrived, but they kindly assigned me the only bedroom with its own bathroom in the carriage house flanking the parking area between the tower and the old stables.

White curtains with embroidered pink roses enclosed thirty-inch-deep window wells at my bed. The sheers poofed with the wind. A patter of rain and blipping of roof water put me to sleep.

This day we met our tour driver, Declan. We’re day-tripping from here. The small tour bus, with windows that opened, was just large enough for our group to hear each other and Declan while we watched the scenes of Ireland unfold. What a treat for me to be able to look around as opposed to being at the wheel.

Today in Castleisland, Declan explained what the Fair Green meant. It is the block in the town set aside for overflow animals on fair day, the main street being for the main market. The Fair Green was also used for overnighting the animals.

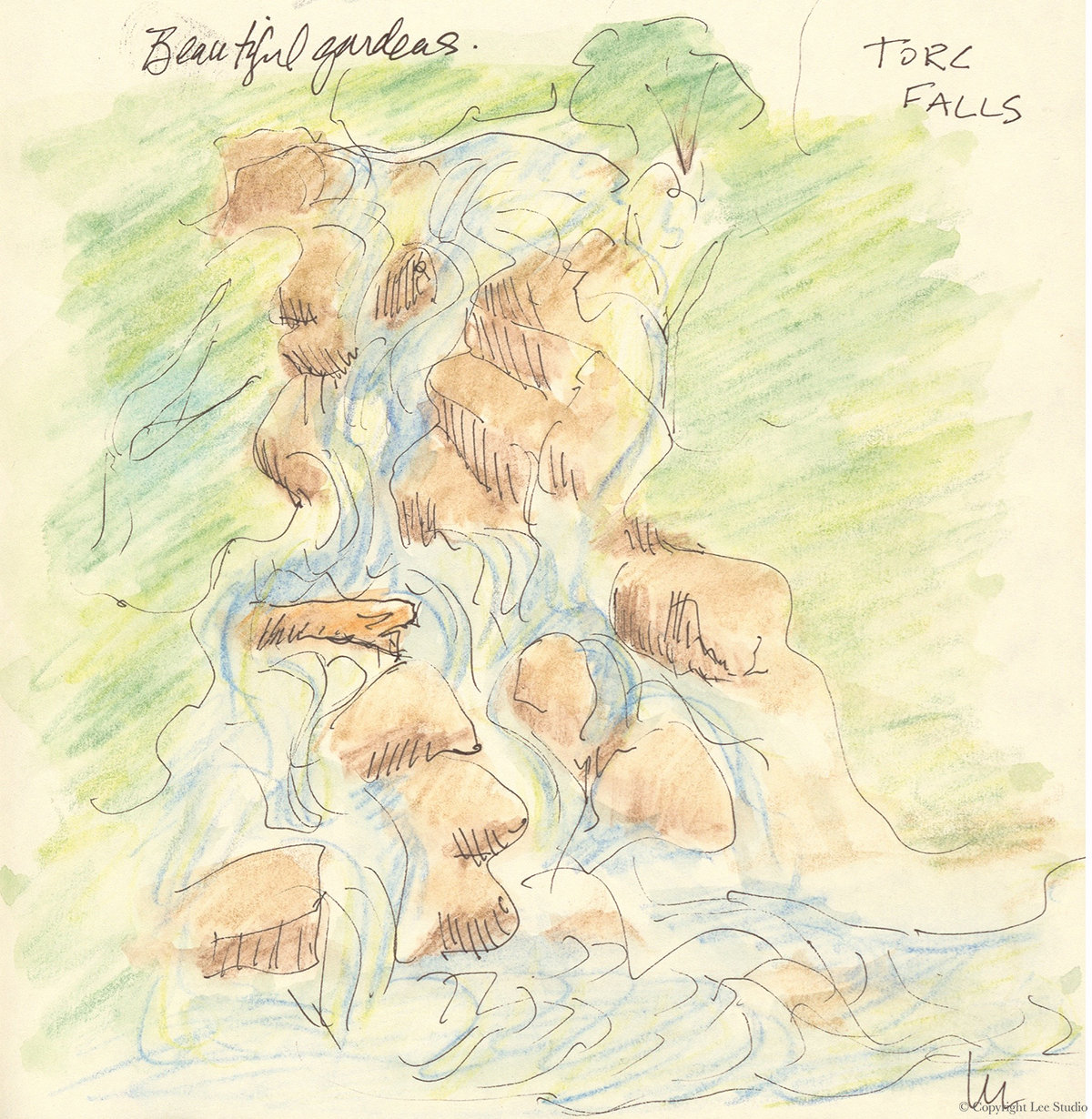

We walked the grounds of Muckross house at Killarney National Park. It bustled with tourists wanting to see the grand house that had been built by a wealthy English family who eventually bequeathed it to the Irish Republic.

It’s not easy for those of us in America to understand the antipathy the Irish have for the English estates and overlords, many of whom still own and occupy estates that had been the land of the Irish people long ago. The impressive long, high, stone walls, old exotic trees, and beautiful mansions are romantically compelling to us since we have little like it in the new world of the United States. To us, they’re romantic and storybook. At first glance, we ordinary Americans are impressed by their size, stature, and power, but we fail to understand the cost in human suffering they represent. Perhaps if we did, we would not laud them so. It begins to sink into our psyche when we learn that the estates are hundreds of thousands of acres. Wait, what? A three hundred-thousand-acre piece of land owned by a single remote English landlord? That toggles our American rebellious reflexes.

To the Irish, the great estates are the edifices of the elite invaders who, over eight hundred years of domination, stole millions of acres of land, miles of fishable rivers, and ruthlessly evicted the native Irish from the land, preventing them from earning a decent livelihood, farming, fishing, studying, or worshipping. Considered peasants by the English, the Irish became their virtual slaves.

For we Americans of Irish ancestry, our desperate, fleeing ancestors were dying to make it safely to our new world. Many perished. Some of us have made it. If they could speak to us, they would have none of it now—fancy castles, great houses, miles of stone fencing that we ooh and aah over in Ireland. We forgot that the English builders of those estates were the elite few, dominating and destroying the many native people in Ireland. It is a cautionary tale for all people and it goes a long way in explaining how native Americans and the people of the First Nations of North America probably feel about European settlers and colonizers who treated them much the same.

On an earlier visit, I learned that the friars and supporters of the church at Muckross Abbey had a long, gruesome history at the hands of the invading English. The abbey was finally destroyed by Cromwellian forces in 1654. An ancient yew tree still stands in the graveyard, but I could not bring myself to cross the yard of so much suffering to see the tree of eternity.